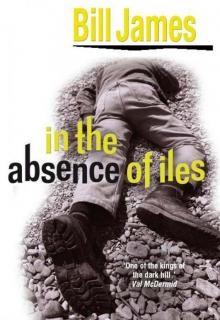

In the Absence of Iles

In the Absence of Iles

Also by Bill James in the Harpur and

Iles series:

You’d Better Believe It

The Lolita Man

Halo Parade

Protection (TV tie-in version, Harpur and Iles)

Come Clean

Take

Club

Astride a Grave

Gospel

Roses, Roses

In Good Hands

The Detective is Dead

Top Banana

Panicking Ralph

Eton Crop

Lovely Mover

Kill Me

Pay Days

Naked at the Window

The Girl with the Long Back

Easy Streets

Wolves of Memory

Girls

Pix

Other novels by Bill James:

The Last Enemy

Split

Middleman

A Man’s Enemies

Between Lives

Making Stuff Up

Letters from Carthage

Short stories:

The Sixth Man and other stories

By the same author writing as

David Craig:

The Brade and Jenkins series:

Forget It

The Tattooed Detective

Torch

Bay City

Other novels by David Craig:

The Alias Man

Message Ends

Contact Lost

Young Men May Die

A Walk at Night

Up from the Grave

Double Take

Bolthole

Whose Little Girl Are You?

(filmed as The Squeeze)

A Dead Liberty

The Albion Case

Faith, Hope and Death

Hear Me Talking to You

Tip Top

Writing as James Tucker:

Equal Partners

The Right Hand Man

Burster

Blaze of Riot

The King’s Friends (reissued as by Bill James)

Non-fiction:

Honourable Estates

The Novels of Anthony Powell

IN THE ABSENCE

OF ILES

Bill James

Constable • London

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson 2008

Copyright © Bill James 2008

The right of Bill James to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication

Data is available from the British Library.

UK ISBN: 978-1-84529-705-3

eISBN: 978-1-47210-592-9

Printed and bound in the EU

PEFC/16-33-111

CATG-PEFC-052

www.pefc.org

Chapter One

Yes, on the whole she liked it best when conferences took place at one of these long-windowed, narrow-gabled, stone-built, converted Victorian country mansions in fine grounds. Well, think of the alternative: some state-of-the-art urban cop shop – the kind she spent most of her life in – all glare-lit corridors and phoney wood doors, except for the cell block. The theme of the conference frightened her. Anything to do with running undercover police operations frightened Esther. The sedate setting might solace her a little. Might. A little.

Most of the renovated old properties were reached along artfully curving drives, tarmacked or gravelled, so the building could not be seen from the gates because of good tree clumps, mostly conifer, oak, larch. The houses had a separateness, had been built purposely to get separateness. Esther fancied a bit of separateness, more or less always did, but rarely got much of it, what with the Assistant Chief job, and Gerald. Of course, there’d been a time when she’d delighted in togetherness with Gerald. She had no trouble remembering those days and nights, but they couldn’t be brought back, although she had tried for a while, and might have another go if things ever got to look more promising. Despite the violence, he definitely still had some good aspects. She worked at encouraging these and never treated Gerald as having become totally fatuous or irrecoverably on the skids.

For now, anyway, she could enjoy the sight and setting of Fieldfare House, this secluded, gracious, secretive rendezvous. About a hundred and fifty years ago, the first, jumped-up creators of estates like this financed the land purchase and construction with magnificent profits from their new factories in hurriedly industrialized towns; or from their coal mines; or from laying railways. They wanted distance between these work sites and their homes, so they could flit from the innovative, cash-flow ugliness to somewhere green and tranquil and private and, of course, with status: the big, solid residences in landscaped, parkland acreage had been pretentious boltholes. A successful labour master would look out on lawns and minor lakes and rhododendron clumps and stables and a paddock, perhaps even on deer, not on the splendid, unsightly enterprises that bought them. Where there was muck there was brass, yes, but the brass would buy a spread where he could forget the muck at weekends. He’d hope, and might believe, his family would be here for centuries, or for ever, the same as dukes at Chatsworth and popes at Rome.

As a matter of fact, no such luck. But Esther Davidson, turning up today at Fieldfare, could sense and enjoy for a moment that former sureness and optimism, and the comfy impression of being apart from the routine tangles of existence. Naturally, she knew the feeling was irrelevant and stupid, brought on only by a classy setting. The feeling came just the same, though, and lingered briefly. And, in the circumstances, there was a bit to be said for this boost to her morale, never mind how temporary and false. What circumstances? Well, during the next three days, Assistant Chief Constable Davidson would be involved in life-and-death presentations and discussions of what an agenda sheet called ‘The Efficient and Secure Management of Out-located Personnel’. In the cause of security, that slab of jargon was very deliberately a slab of jargon, and very deliberately unintelligible.

Decoded, it said: How to place an undercover detective in a targeted gang, cell, clan, crew and make certain (by – see above – due Management) he/she (a) comes up with enough stuff usable at trial to convict on (i.e. – see above – is Efficient) ; and, above all, (b) stays undiscovered, untortured, and unsunk in a concrete bodysock (i.e. – see above – is Secure).

‘Out-located’ meant one very precise thing, and, also, its very precise opposite. True, the officer would be Out-located from family, from normal duties, from usual colleagues and, crucially, from standard life-lines and protective back-up. But this was in order that he/she could penetrate a crooked team – could, in fact, be deeply and secretly In-located: that is, become part of, or seem to, the targeted gang, cell, clan, crew. It would usually be a gang, cell, clan, crew, that had shown itself unbeatable, unsmashable, unjailable, over at least months, and more likely years, by any other police method. Standard investigative ploys will have done nothing. Because of the hellish, continuous perils, you tried every alternative before deciding to install a spy. And if you got that far you prayed the secrecy would last, and had a unit ready to go in and recover the officer i

n time, if it didn’t. Or try to recover the officer in time. Esther knew that very soon she might have to smuggle one of her people into the biggest, most savage, enduring, prospering and expanding criminal firm back on her own ground. She hated the notion, but maybe at Fieldfare she’d learn something handy and extra and reassuring, to go with what she’d learned already from other undercover gambles.

The original got-rich-quick occupant of Fieldfare House could never have visualized what actually would happen to his grand, deserved, dignified property. So, what did? Time happened. It wasn’t unique. Those who came after the mighty industrialist would eventually, or sooner, have found the place too costly to run and maintain. They’d begin to think about the comforts of suburbia, and soon the removal vans would roll. Servants for a place like this, and central heating and damp courses and tonnes of re-roofing slates, could grow unacceptably expensive. The Home Office – the Home Office – intelligently interested itself in such homes or ex-homes and bought Fieldfare and its surrounds at not much above peanuts. Then, after thorough repairs and decent refurbishment, turned it into a venue for the kind of sometimes dark, sometimes unnerving get-togethers Esther and colleagues from the Association of Chief Police Officers nationwide had been invited to now.

Chapter Two

Thursday 22nd June 2006, 1400 hours, Simpkins Suite Out-Located Operations: Two Personal Narratives

Officer A: 1400–1500 hours

1500–1530 hours, Questions

Officer B: 1530–1630 hours

1630–1700 hours, Questions

Esther tried to recall from school history lessons whether any of the great Industrial Revolution contractors had been called Simpkins; possibly not quite as renowned as Watt or Arkwright, but important. To christen one of the rooms after Fieldfare’s original owner would be a nod to scholarship which might appeal to some knowledgeable Home Office dignitary, and there were a few of those. Did Alfred or Samuel or Bertram Simpkins invent an early version of the fork-lift truck? Should she have heard of ‘The Simpkins Hercules Hoist’?

There were civilian staff at Fieldfare, of course, all excluded from the Simpkins Suite and other Suites while sessions about Out-location took place. Just the same, there might be leaks. And so, the two featured officers who had been undercover, and who might go undercover again, appeared merely as A and B when they gave their ‘personal narratives’: that is, described and analysed their Out-located experiences for this gathering of brass; no names and no indication of which part of the country they worked in. A and B’s ranks, as well as their names, remained undisclosed. But, almost certainly, they’d be detective constables only, or, at the highest, detective sergeants. Years ago, as a detective constable, Esther herself did some Out-location, slangily known then, though, simply as ‘leeching’.

She wondered whether A and B found it daunting to take the platform and instruct a roomful of Association of Chief Police Officer members. But was that crazy? After all, A and B had lived for weeks, even months, in situations needing a stack more bravery than confronting an ACPO collection. Nobody at Fieldfare would put a knife to their throats, a daily and nightly chance for Out-located detectives. Esther had never known more fear than when undercover.

Officer A: Meet Mr Adjustable

He’d be about twenty-eight or -nine and before saying anything catwalked back and forth like a model on the small, temporary platform at the end of the room. Occasionally, he pirouetted, so they could take in the all-round glory of his three-piece, double-breasted, grey suit, which was all-round glorious. Unquestionably, it had been custom-made. The cloth held to his shoulders in the affectionate, unruffled, congratulatory way a midwife might present a just-born baby to its mother. The lapels were mid-width and timeless, no ludicrously sharp, wool spear points at the top. Not much of the waistcoat showed under his buttoned-up jacket, but Esther could tell it fitted right, and the pockets contained nothing bulky to destroy the general line. His striped blue, white and aubergine silk tie had impact without luridness. She thought A’s black lace-up shoes would be from Fellowes, or Mason and Caltrop, and possibly also custom-made. He’d had his hair done in a moderately up-tuft style, but, again, nothing coarse, nothing farcical. You could see men with haircuts like this presenting unextreme television programmes or running charity shops.

He came to the edge of the platform and gazed at them: ‘You might have to shell out on this kind of tailoring and so on,’ he said. ‘It’s all paid for by the police. I’ve got three outfits of similar quality, two K a throw, and a stack more shoes. Upper grade villains dress upper grade. And conventional. You’ve got to match it on your boy – on your girl, too, if you decide to pick female, though gangs tend to be male and sexist, and the rules for what women wear are different.’ Esther couldn’t pinpoint any accent. He grinned. ‘So, you have to wonder, could you afford me?’

He assumed instant charge of the Simpkins Suite. A Simpkins descendant couldn’t have been more at home. For God’s sake, Esther had madly imagined he might be nervy and hesitant in front of them! She realized he reminded her of someone, not the actual looks but his radiant cockiness. In a moment, she pinpointed who: Joel Grey, as the singer and club master of ceremonies, in that Liza Minnelli film, Cabaret, on DVD. She saw the same mixture of lavish insolence and impishness in Officer A. His voice, the glare of his eyes and the aggressive, challenging tilt of his modish head said he didn’t recognize much of any real worth in this puffed-up audience and thought they might as well push off right away, back to their snug, well-pensioned, desk-bound sinecures. He had lived in, survived in, a rough, non-stop dangerous scene, and might have to again. They needn’t expect any kowtowing from him. He couldn’t know that Esther, and perhaps others in the room, had also entered that dangerous scene in the past. He shot the cuffs of his stupendously white shirt. Gold links flashed, like ‘Fuck the lot of you’ in Morse.

But then he turned his back for a moment and when he slowly spun and faced them once more seemed suddenly . . . seemed suddenly what she’d originally expected: nervy and hesitant. In small, arse-licking, sing-song tones he said: ‘Ladies, gentlemen, this is a privilege and an important responsibility to address so many chief officers.’ His body signalled prodigious cringe now. The suit had somehow abruptly lost its oomph and might have been an entirely ordinary, reach-me-down, sixty-quid job. You could suspect him of having pinched at least the cuff-links, and possibly the shoes. ‘I speak for my colleague, B, and myself,’ he went on, ‘in saying that we are, indeed, surpassingly grateful for the interest shown in our work by high representatives from so many British police forces. I – we – are honoured by such interest, which will encourage, nay, inspire us, when next we are required to take on infiltration assignments. It is especially appropriate that this valuable endorsement of our special duties should occur in the magnificent Simpkins Suite of the renowned Fieldfare House, a symbol of success in another era through boldness, vision and effort. These are characteristics which B and myself will seek to emulate, in this twenty-first century, deeply heartened by your presence here today.’

He smiled a minion’s greasy smile, and passed the tip of his tongue gingerly along his upper lip, like playing the word ‘lickspittle’ in Charades. Now, when he flashed his cuffs and the links, the gesture seemed pathetically boastful – a desperate ploy by someone frantically struggling to come over as significant.

Esther realized they were watching a performer who could have made it big in the theatre. He did roles, inhabited them instantly, no matter how different from one another. During her days at Fieldfare, Esther would several times run across the word ‘protean’, meaning able to change appearance and character at will. And A seemed to have decided to give a demonstration of this flair, or had been instructed to, so Esther and the rest of the audience would know the kind of talents they must demand in their undercover people. Next for A, King Lear. Or Bottom. Just tell him what you wanted. He brought out crummy words like ‘nay’ and ‘indeed’ without a tremor

. He was made for Out-location, In-location. That is if, as well as his acting range, he knew what to look for, and remembered it, and brought it back in a form fit to prop a prosecution.

He might never appear on the witness stand himself, or that could be the end of him in secret operations. Might be the end of him altogether: relatives and friends of those he helped send down would want a reckoning if they saw plainly and painfully at trial how they’d been gulled. But A, and those in his game, must be able to guide and brief and cue the colleagues who could do the arrests and give the evidence in court. He, personally, would stay out of sight, watching his back, counting his suits, cooking up insults and smarm for his next appearance at Fieldfare.

Judges sometimes turned nosy and obstructive in cases based on undercover evidence. Of course, judges would never be told the prosecution rested on undercover evidence. Those words – ‘undercover’, ‘Out-located’ – had to be kept from the wise; the allegedly wise. But some of them tactlessly sensed or sniffed out gaps in material as it came before the jury. A detective in the box might say that, ‘acting on information received’, he turned up at the right place and at the right time to witness the accused doing what he was accused of, and to arrest him. ‘On information received from where and how?’ some intellectually unkempt judge might ask. Because the source had to stay confidential, no proper answer could be given, and there were judges who regarded this as either an affront to themselves and therefore to the whole edifice of British justice, and/or cool defiance of themselves and therefore of the whole edifice of British justice. They regarded spying as a sneaky, obnoxious trade, unless done years ago by Alec Guinness in Smiley’s People on BBC television. The prosecution case might get thrown out. Undercover people accepted this as customary, high-minded, wig-powered, Inns of Court absolutism and idiocy, and waited for the next casting, or promotion into Traffic.

Subsequently today, Officer A turned philosopher and theologian for a while. For this, he put a real whack of solemnity into his voice and manner. ‘Think the movie, Reservoir Dogs,’ he said. ‘Think ethics, think acute and inevitable spiritual confusion. Consider how your man or woman undercover must in the interests of his/her disguise temporarily become a villain, going enthusiastically along with all kinds of gang crimes, including possible murders. Will that be acceptable to you? If not, perhaps you should forget undercover capers. Do it some other way. For credibility, and to see offences at first hand, your planted officer might have to take part in the actual lawlessness he/she has gone undercover to expose and thwart. His/Her Honour, concerned to guard his/her honour and the court’s, will possibly disapprove of such dishonourable behaviour, if Her/His Honour should get sight of it. He/she might find it hard to believe the supposed good end justifies the dirty means, and QCs climbed to be QCs by highlighting the dirty means so judges did notice them; unless the QCs were hired by the Prosecution, in which case they’d downplay the dirty means, naturally, and try to blank off the judge from them.